The Saassy Guide to Go-to-Frameworks for your Go-to-Market

When I started out in software, I loved figuring out go-to-market strategies and launching new products. I did a lot of research and relied on data, which gave me comfort in my decision making, but I was winging it. Here’s a list of the top frameworks I wish I had back when I started.

What is Go to Market?

Let’s define what a go to market is: a comprehensive plan to bring a new product or service to market. A lot of work and many different components go into creating GtM (check out this comprehensive list). In this blog, I will focus on four: target market, positioning, pricing, and the acquisition plan.

Component 1: Target Market

My favourite framework: Jobs to Be Done (JTBD)

Why: As a marketer, I grew up on Personas. But later, I discovered a framework that is still rare in marketing yet well known within product management and design: Jobs to Be Done (JTBD). And I converted immediately.

Personas focus on attributes rather than motivations and desired outcome. I found difficult to market around Personas. On the other hand, JTBD reminded me of a value proposition - once the JTBD was done, the rest of the marketing plan almost drew itself.

In addition, focusing on attributes instead of motivations and desired outcomes may lead to a wrong target market altogether. Custom Tobacco is a case in point. A cigar company, they targeted cigar smokers but were barely getting any orders. Soon they uncovered two key insights: (1) cigar smokers were extremely brand conscious and loyal; and (2) the orders that they were getting came from gift givers and event planners. Turns out their target audience were not the smokers, but people buying cigars as a gift. This completely changed how Custom Tobacco was developing and marketing cigars.

Personas explain who people are and what people do. But they never fully explain why people do something. And why people do things is far more important.

Paul Adams, CPO, Intercom

What is it: JTBD is a framework for mapping out your customers’ needs and the goals they want to accomplish. It helps you figure out the jobs that they are hiring your product to perform. There are three key components:

A Job to Be Done Statement, a high-level description of what the user is trying to accomplish, the context, the job, and the ideal outcome;

A Job Map that breaks the Job to Be Done down into eight distinct steps and activities a user has to complete to achieve their goal;

A Desired Outcome Statement that can accompany the overall JTBD and each step within the Job Map. These statements include criteria a customer uses to evaluate whether the job is well done.

Once we have mapped the JTBD and desired outcomes, we can understand where the opportunities lie, and where existing solutions are underserving customers. We can simply uncover this by asking customers two questions: “How important is this for you?”, and “To what degree are you satisfied with the existing solutions?”

Using this methodology, Coloplast figured out which customer needs were underserved by the market and its competitors, creating a truly differentiated outcome-based value proposition, leading to a fast double-digit growth. Coloplast found that most of the underserved needs for its wound care products related to preventing healing complications - while competitors focused on fast healing.

Key Resources

Tony Ulwick’s walk-through of the Jobs to Be Done Framework

Intercom’s case study on using JTBD in marketing and GtM

The Saassy Guide to... Personas are dead, long live their problems

Component 2: Positioning

My favourite framework: Obviously Awesome

Why: Positioning is hard because it has a lot of inter-dependent ingredients: your strategy and vision, your competitors, your target market needs and characteristics, your product and competitive advantages … No one ever knows where to start.

In addition, what exists today, isn’t helpful. We all have been given a positioning statement template with blanks to fill in. These templates assume you already have the answers, so it omits any guidance as to how to get to them.

April Dunford’s framework doesn’t give you any template to fill in. Instead it gives you a clear, practical ten-step process to come up with a killer positioning.

What is it: April’s positioning has five components: competitive alternatives (this is defined broadly, not just the competitors you track but anything customers could use instead, including pen and paper), unique attributes you have compared to these alternatives, value and proof (what these attributes enable for customers), target market characteristics, and market category (the context setting for your customers).

I won’t go through the ten steps that April’s positioning process entails, but this is what I like about it:

It is customer-centric: The process is outward-looking. Pretty much every step is about how customers perceive you, what they appreciate the most, which customer segment matches best with what you have to offer.

It focuses on value, not technicalities of features: The process still includes listing all the features your product has over your competition, but it is just an interim step. The end goal is to analyse what benefits these features enable for the customers.

It leaves ego at the door: Positioning exercises often go wrong or are not adopted because they are carried out as an isolated effort. Obviously Awesome highlights it is a cross-functional work with any positioning baggage left behind.

Key resources:

April Dunford: Obviously Awesome

Component 3: Pricing

My favourite framework: Ramanujam’s and Tacke’s Monetizing Innovation & Reforge

Why: Maybe we settled on pricing because we needed the extra P for the 7 Ps of marketing, or to go with the P of Packaging. But pricing is limiting because it only cares about “how much?” That’s why I prefer the term monetization.

What I love about both Reforge and Monetizing Innovation is that they push pricing into a strategic lever of the business GtM strategy. It is not just an excel sheet exercise.

What is it: There’s not a single framework to highlight in this case. Instead, a lot of great principles, frameworks and tactics to solve any pricing challenge, and get you think strategically - even if you don’t have the resources to run a fancy Van Westendorp pricing survey or MaxDiff.

Ramanujam’s and Tacke’s Monetizing Innovation

Ramanujam and Tacke go through nine key principles for monetizing innovations, guiding you to avoid key innovation failures: cramming in too many features, under-pricing a very valuable feature, a feature that had a great potential but wasn’t brought to the market properly, or a feature customers didn’t want.

“New products fail for many reasons. But the root of all innovation evil is the failure to put the customer’s willingness to pay for a new product at the very core of product design.”

Madhavan Ramanujam and Georg Tacke: Monetizing Innovation

A couple of the key insights I’d love to highlight:

Have the willingness to pay talk with customers early - it informs a lot of product and GtM decisions (sometimes even if you should actually build the product, to start with!);

Segment, segment, segment: Imagine there are two groups of customers. Group A would pay $20 for the feature, and group B would pay $100 for the same feature. Doing averages, you’d charge $60. But that means that the feature is still too expensive for group A, whilst you are leaving $40 on the table per customer from Group B. Solution? Different packaging, pricing and positioning for different customers, based on their willingness to pay.

Communicate the value of your offering: value-based pricing focuses on the upside of your offering, it establishes the upper ceiling. It enables your customer to see the good stuff your product offers. It enables you to charge premium and break away from competitive comparisons.

Reforge Monetization & Pricing

Reforge breaks down the scary pricing (and even scarier monetization) into building blocks and then guides you how to put them together. It is hard to filter just a couple of key frameworks to highlight, but these two are some of the building blocks in my eyes.

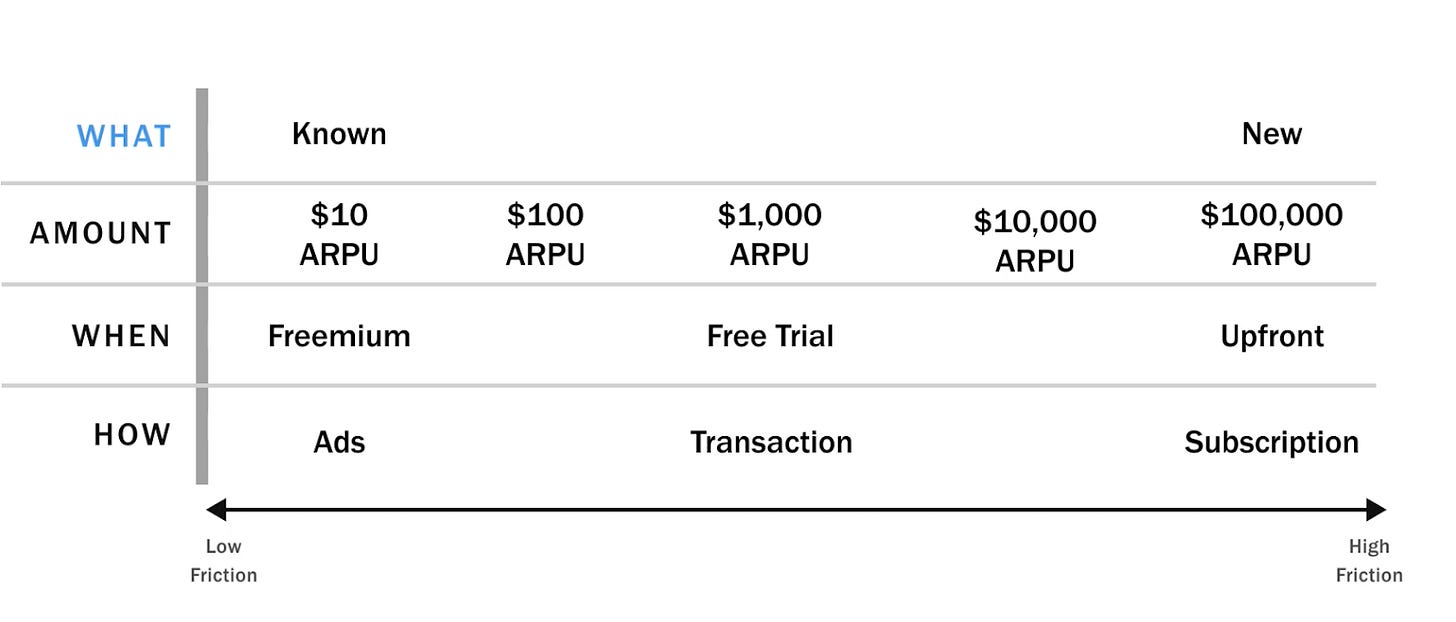

First of all, any monetization decision is composed of four key components:

The value metric - i.e., how the price scales. Do you charge per a user, or the outcome (e.g., number of tables booked), or features?

The price itself

What do you charge for - i.e., the packaging

When do you charge - never (free), transactional or subscription (if so, at what frequency)?

Every time you make a monetization decision, you have to consider three aspects:

Consumer view - are they willing to pay? what do they value? when do they want to pay?

The impact or the friction your monetization could add to your business model

Cost of revenue - is your revenue going to cover the cost of acquisition and cost of serve?

Key resources:

Madhavan Ramanujam and Georg Tacke: Monetizing Innovation

Lenny’s Podcast: The Art and Science of pricing with Madhavan Ramanujam

Lenny’s Podcast: How to Price your Product with Naomi Ionita

Reforge: Monetization & Pricing

Component 4: Acquisition plan

My favourite framework: Reforge Four Fits Framework - Model Channel Fit

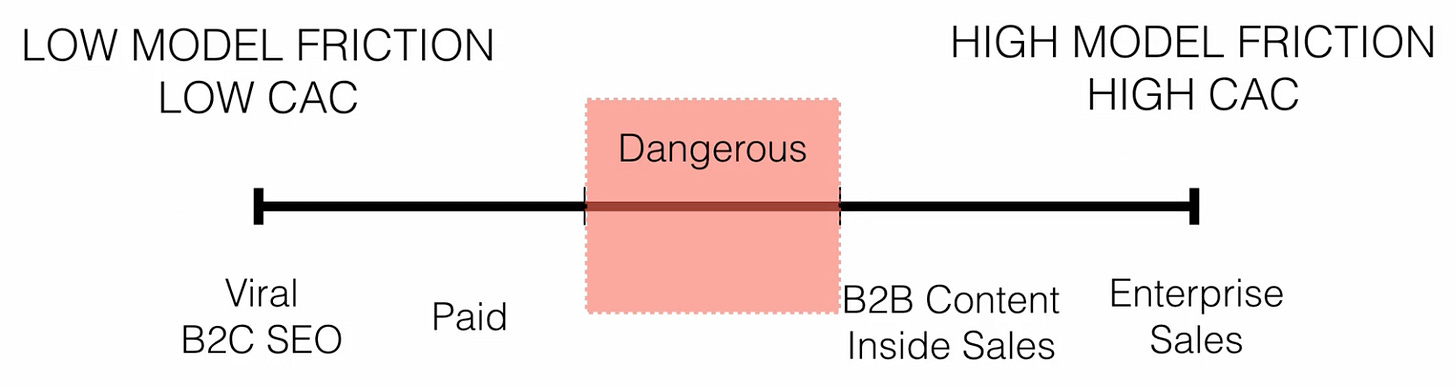

Why: We often fall into a trap when launching a new product to leverage whatever acquisition strategies and tactics we already have in place. Typically, we only focus on picking the right channel for the audience we are after. What I love about Reforge’s four fit model is that it opened my eyes to matching the acquisition strategy to other aspects of the overall business strategy - rather than just the audience.

What is it: Reforge Four Fit model has four aspects: the market, the product, the monetization model and the channel (acquisition), and they all have to align.

The idea of the monetization model - channel fit is simple: the different elements of monetization introduce different levels of friction. You have to pick those acquisition tactics that have enough power to push users over the level of friction. In general, the higher the cost of the channel, the more influence it has on the user. This means that you have to align low CAC channels with low friction model, and high CAC channels with a high friction model.

The friction of the monetization model follows a spectrum. On the low friction end, you’d find a freemium model for a known product with a very low subscription with a short payment cycle (i.e., you can cancel any time). Because it is so easy for the user to start using the product, we need very cheap acquisition tactics such as virality or user generated content. On the other end of the spectrum, high friction, you will find large enterprise deals which require a long procurement cycle, a decision by a committee of executives, a complex implementation and upfront costs. Users here need a lot of “encouragement” to start using your product, so you need a high CAC tactic, such as trade shows and enterprise sales.

If your monetization and channel don’t align, either your model doesn’t bring in enough revenue to support high CAC, or you don’t have strong enough acquisition to get users over the friction.

Key resources: